Night Flight Time Calculator

The Calculator App

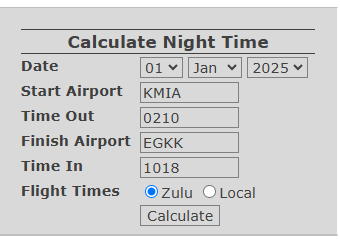

This app calculates the amount of flight time that occurred during "official night" on any flight, using the aircraft's departure and arrival times and locations.

Enter details of a flight below and select Calculate to see the night flight time. If the 4-character ICAO code for either aerodrome is entered, the form will automatically retrieve the Aerodrome Reference Point latitude & longitude values.

Total Flight Distance: {{nfCalculation.flight_distance | number: 0}} nautical miles

Flight Duration: {{nfCalculation.total_flight_time}}

Average Ground Speed: {{nfCalculation.avg_ground_speed | number: 0}} knots

Night Flight Time: {{nfCalculation.night_flight_time}}

Civil Twilight Transitions:

- Time: {{x.time}} Z

- Lat: {{x.position[0] | number: 3}}°

- Lon: {{x.position[1] | number: 3}}°

- Time: {{x.time}} Z

- Lat: {{x.position[0] | number: 3}}°

- Lon: {{x.position[1] | number: 3}}°

Take-off at Night? {{nfCalculation.night_takeoff}}

Landing at Night? {{nfCalculation.night_landing}}

How the Calculator Works

The Night Flight Calculator app determines the amount of night flight time by generating a Great Circle model of the flight and using this to determine whether the flight either took place all during daytime or night-time, or transitioned from day to night and/or night to day during the flight. The app iteratively checks for any day-night transitions and then returns the total number of minutes of the flight when the conditions were "night".

The calculator has been built to fill a current gap in aviation logbooks, namely a precise and reliable means of determining the portion of a flight that occurred during night conditions. At time of writing, there is a substantial lack of accuracy and consistency in the way most pilots calculate their night flight hours. The aim of this calculator and the research below is to provide the aviation community with a mathematically-sound, best-practice method of calculating an approximate aount of night flight time for any flight, accurate to the nearest minute. It is hoped this application can go some way to providing clarity and consistency in this area of logbook record-keeping.

To read more about how the app works and the mathmematics behind it, please select from the table of contents below.

Table of Contents

- The Calculator App

- Introduction

- Definitions

- Current Methods of Determining Night Flight Time

- How to Calculate Night Flight Time

- Study Conclusions

Introduction

Licensed aircraft pilots are required to maintain a record of all their flight training and flying experience. This record is known as the pilot's Logbook. The particulars of each flight that must be recorded in the logbook are mandated by national and/or regional aviation regulatory bodies, like EASA (Europe) and the FAA (USA). These include: departure and arrival aerodrome, the flight time, aircraft type, etc. Major international regulators, including EASA and the FAA, also mandate that pilots must record the amount of flight time accumulated during night-time – see EASA regulation FCL.050 and FAA regulation CFR 14 Part 61.51 .

Historically, pilots logbooks have consisted of paper-based ledgers, with particulars of each flight written in by hand and totalled at the bottom of each page (example shown right). Logbook accuracy is essential, as a pilot's licence privileges are directly limited by their flying experience. When applying for more advanced flying licences, pilots are usually required to submit their logbooks for scrutiny, so they must ensure their logbooks are both complete and as accurate as possible.

For parameters like night flight time, this is not always straightforward. ICAO defines night-time as, "the hours between the end of Evening Civil Twilight and the beginning of Morning Civil Twilight", which seems fairly clear-cut and for local flights taking off and landing at the same aerodrome, it is straightforward for pilots to lookup the civil twilight almanac times for a particular day and calculate their night flight time accordingly. The difficulty comes when looking at longer flights, particularly long-range, high-speed commercial flights travelling between aerodromes. For these flights, where is civil twilight is being measured from? The departure aerodrome? The arrival aerodrome? Halfway between the two? On such flights, the time of sunset at the departure aerodrome may be very different to the actual time when sunset is first encountered and regulatory guidance on the matter is currently lacking.

In practice most pilots, including commercial pilots, will use rough approximations for their night flight time, based on observed flight conditions – literally, "how long was it dark outside for?". Pilots may even round the night flight time to whole or half-hours to make adding up the totals in their handwritten logbooks easier! Such methods obviously lack any sound mathematical basis, with the result that the night flight hours recorded in traditional paper logbooks are likely to be substantially inaccurate. As well as being undesirable, this also creates the opportunity for pilots to artificially inflate their night-time flying experience.

The problem has been partially alleviated with the rise of portable electronic devices and web-based flight tracking applications. These have allowed many pilots to switch from paper ledgers to electronic logbook applications. Aside from being faster and more convenient, several of these electronic apps automatically calculate the flight particulars, including night flight hours, which improves accuracy and restricts the ability to inflate experience.

These recent improvements have not completely solved the problem, however, because at the time of writing the Author is unaware of any standard method for calculating night flight time when flying between two different aerodromes. Existing electronic logbooks with tools for automatically calculating night hours appear to use a variety of different logic in their calculations, with the result that asking two platforms to calculate night flight time will generally result in two different answers!

Hence, the aim of this application and associated research in the study outlined below, is to provide an accurate and mathematically verifiable "gold-standard" methodology for calculating night flight time for any given flight.

The research below examines the following:

- Existing pilot logbook systems and the current gaps that exists in logbook accuracy with respect to night flight time;

- The mathematical theory used to determine "Official Night" and the portion of a flight that occurred at night;

- The practical assumptions about aircraft route and speed that must be made in order to calculate night flight time;

The study concludes with a summary of the mathematical steps and best-practice assumptions that can be used to accurately determine night flight time, along with a recommendation for aircraft manufacturers to further improve this solution.

Definitions

- ICAO: The International Civil Aviation Organization.

- EASA: The European Air & Space Agency, regulators of air travel in the European Union.

- FAA: The Federal Aviation Administration, regulators of air travel in the USA.

- Civil Twilight (Morning/Evening): The moment when the geometric centre of the sun is 6 degrees below the horizon. Morning Civil Twilight occurs when the sun rises through 6 degrees below the horizon and Evening Civil Twilight occurs when the sun descends through 6 degrees below the horizon.

- Night Time: ICAO defines night time as the hours between the end of Evening Civil Twilight and the beginning of Morning Civil Twilight. Note that individual authorities may specify alternative definitions. This study shall only consider the definition related to Civil Twilight.

- Flight Time: The total time from the moment an aircraft first moves for the purpose of taking off until the moment it finally comes to rest at the end of the flight. Note: Flight time as defined here is synonymous with the term “block to block” time or “chock to chock” time, which is measured from the time an aeroplane first moves from its parking position for the purpose of taking off until it finally stops at its arrival parking position at the end of the flight.

- Night Flight Time: Flight Time accumulated when the flight conditions are "Night Time".

- Aerodrome Reference Point/ARP: The exact geographical location of an aerodrome, usually near the geometric centre of the aerodrome.

- Logbook: A record of a pilot's training and aeronautical experience, containing particulars of each individual flight or series of flights that a pilot has carried out.

- World Geodetic System 1984 (WGS 84): A 3D coordinate system that defines the Earth's shape and location. It is the standard coordinate system used for navigation, mapping, and positioning by ICAO.

- Great Circle Track: The great circle track represents the shortest and most efficient path between two points on Earth.

- Ground Speed: The speed of an aircraft relative to the surface of the earth.

- Blocks Off/Chocks Off Time (Departure Time): The time when an aircraft leaves its parking position to commence taxiing for departure.

- Blocks On/Chocks On Time (Arrival Time): The time when an aircraft reaches its final parking position after landing and engines are shut down.

- Julian Date: An astronomical term, where the date is represented as a single the number of days since the beginning of the Julian Period (4712 B.C.), plus the fraction of a day since the preceding noon in Universal Time.

- FMS/Flight Management System: An onboard computer that automates a range of flying tasks, including navigation, flight planning, and aircraft performance.

Current Methods of Determining Night Flight Time

The author has interviewed various pilots and researched numerous electronic applications to determine the methods currently available for calculating night hours on a flight. The most common methods currently in use across the industry are:

- Use of Astronomical Almanacs for Civil Twilight times

- Pilot observation and approximation in paper logbooks

- Automatic calculation by electronic logbook applications

Astronomical Almanacs

Astronomical Almanacs are freely available online and can be used to lookup the exact time of Morning & Evening Civil Twilight for any combination of date, latitude & longitude. An example Almanac is TimeAndDate.com. Knowing the civil twilight times at an aerodrome can allow the night portion of a flight to be calculated as the period of the flight when the aerodrome was in night time conditions.

Example:

- Aircraft departs EGTK (London Oxford) at 17:00Z on 3rd February 2025, returns at 18:00Z;

- Evening Civil Twilight at London Oxford Airport on 3rd Feb 2025 ends at 17:33Z (from Almanac);

- Total flight time = 60 minutes; Night flight time = 27 minutes (17:33-18:00Z).

For aircraft that depart, then remain local to or arrive back at the same aerodrome, this method is highly accurate. Unless the aircraft travels a considerable distance from the start point immediately before or after civil twilight periods, errors are unlikely to be more than a few minutes.

At present, this method is commonly used by private pilots and student pilots, whose flights frequently depart and arrive at the same aerodrome. It should be considered an accurate and reliable method; ironically, much more accurate than the raw observation and estimation used by many commercial pilots!

Pilot Observation

For commercial flights travelling over longer distances, knowing the civil twilight timings at either end is less useful for the reasons discussed in the introduction above. Traditionally, commercial pilots using paper logbooks will resort to simple observation when estimating their night hours, ie: estimating the portion of a flight that took place in darkness. This method clearly lacks any scientific rigour; added to which are the common cases of pilots rounding the estimated night hours to whole or half-hours, for convenience when totalling their logbook hours later on!

This method of estimating night flight time is at best inaccurate, and at worst an opportunity for deliberate inflation of night hours. Despite this, it is probably the most common method used by professional airmen, particularly those that retain paper logbooks. This reality should perhaps encourage airlines and regulators to promote or even mandate the use of electronic logbooks with automatic night time calculators, both to improve accuracy and reduce the risk of hours manipulation.

Automatic Calculation

Electronic logbooks offer convenience and greatly improved accuracy by providing automatic calculation of night hours. An example shown right is provided online by CrewLogbook.com.

The tool performs several calculations to determine civil twilight times at departure and arrival aerodromes. The output looks like this:

Closer inspection of the results above reveal that although the tool is able to determine day-night or night-day scenarios, the calculation of the night portion of the flight isn't quite right. It is probably the time between sunrise (not start of morning civil twilight) at EGKK and the flight's arrival into EGKK, 2 hrs and 9 minutes later (the "Day" portion of the flight).

A variety of electronic logbook tools provide a similar automatic means of calculating night hours, but without detail on the mathematical methods used, or its levels of accuracy. The next section compares the output from several of these tools for a series of fictional long-haul flights.

Testing Existing Calculators

Electronic apps that automatically calculate night flight time can significantly improve pilots' logbook accuracy. Results may vary, however. The Author is not yet aware of a common mathematical method for calculating night flight time, with the result that asking several different calculators to calculate night flight time will generally result in several different answers.

The table below shows the results of investigations into several popular Electronic Logbook applications currently available to pilots. It compares the calculated night flight time for a series of fictional, but realistically timed, long-haul flights:

| Departure Aerodrome | Arrival Aerodrome | Departure Date/Time (GMT) | Arrival Date/Time (GMT) | Total Flight Time | Calculated Night Flight Time by Existing Applications | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PilotLog.co.uk (MJICCS Ltd.) | CrewLounge.aero PilotLog | flylog.io | Pilot Pro (Labrum Co.) | CrewLogbook.com | Logbook.aero | This Calculator | |||||

| Miami KMIA | London EGLL | 20 Mar 2025 20:00Z | 21 Mar 2025 06:00Z | 10h 00m | 6h 55m | 7h 22m | 6h 46m | 9h 30m | 8h 20m | 6h 47m | 6h 46m |

| New York KJFK | Athens LGAV | 20 Aug 2025 20:00Z | 21 Aug 2025 10:00Z | 14h 00m | 5h 56m | 6h 31m | 5h 45m | 13h 12m | 11h 07m | 5h 45m | 5h 46m |

| Stuttgart EDDS | Mexico MMMX | 20 Dec 2025 15:00Z | 21 Dec 2025 03:00Z | 12h 00m | 9h 42m | 11h 13m | 8h 29m | 8h 30m | 11h 36m | 8h 32m | 8h 39m |

| London EGLL | Cape Town FACT | 20 Oct 2024 12:00Z | 21 Oct 2024 00:00Z | 12h 00m | 6h 31m | 7h 00m | 6h 37m | 5h 00m | 7h 08m | 6h 39m | 6h 40m |

The results from the survey show a surprisingly wide disparity between different automatic night flight time calculators provided by electronic logbook apps. Some calculators appear to significantly overestimate night flight time and none agree exactly with one-another. This highlights the current lack of a standardised, mathematically sound method for calculating night flight time.

Two of the applications tested provided very consistent results, both with each other and with this calculator. These were:

This would suggest that these calculators employ a very similar approach to modelling flights and calculating night flight time to that described below in this study. The following chapters discuss how best to "model" a flight, the assumptions that are needed to create a practical model, and the mathematical steps to calculate night flight time from the flight model.

How to Calculate Night Flight Time

The sections below outline the mathematical steps used by this night flight calculator to compute the portion of any flight that occurred at night. A summary of the calculation steps is as follows:

- The flight is modelled as a " Great Circle" track between departure position and arrival position;

- Solar Elevation is calculated at the beginning and the end of the flight is;

- The flight is divided into discrete 10-minute time segments;

- At each 10-minute interval, the modelled flight position is calculated and Solar Elevation is determined at that position;

- If a day→night or night→day transition occurred, the calculator will further divide the 10-minute time segment into individual minute segments to determine the exact time of day→night/night→day transition, ie: the exact minute when evening civil twilight ended or morning civil twilight started;

- With the exact times of day→night and night→day transition, and the day or night condition known at the beginning and end of the flight, the calculator adds up the time portions between each night period and returns the total night flight time.

Definitions of Night

Before the mathematics is discussed, a brief expansion of the ICAO definition of night:

ICAO defines "Night Time" as the period of time between the end of Evening Civil Twilight and the beginning of Morning Civil Twilight. Evening Civil Twilight and Morning Civil Twilight are meteorological terms:

- Evening Civil Twilight refers to the time between the Sun's geometric centre being between 0 degrees ("sunset") and 6 degrees below the horizon ("end of evening civil twilight").;

- Morning Civil Twilight is the reverse, where the Sun's geometric centre is between 6 degrees below the horizon ("start of morning civil twilight") and 0 degrees ("sunrise").

In other words, the flight conditions are considered to be "night" any time the Sun's geometric centre is 6 degrees or more below the horizon, ie: \({Solar \; Elevation} \leq -6^o \).

Required Assumptions for Practical Calculation

As discussed above, determining whether the flight conditions are "day" or "night" is a relatively simple process of calculating the Solar Elevation for a given time and position. The difficulty arises when we consider the fact that an aircraft is generally always moving, often at considerable speed. This raises the questions of exactly when and where the aircraft will be when we are determining Solar Elevation.

Modern long-haul flights can cover a substantial distance of the Earth at tremendous speed for substantial periods of time. This movement will continuously alter the position of the aircraft and hence the time of sunrise, sunset, and evening & morning civil twilight throughout the flight. Consider the following scenarios:

- Flights that depart in daytime and transit through the civil twilight boundary between day and night, arriving at their destination at night, and vice-versa;

- High-speed flights at high latitudes, which cross multiple civil twilight boundaries during a flight, transitioning from day to night and back to day again;

- Supersonic flights, and near-supersonic flights travelling at high latitudes and moving faster that Earth's rotation, thereby transitioning from night to day;

- Flights that directly cross Earth's Poles, with unusual day-to-night and night-to-day transitions.

As this list suggest, it is difficult to divine a perfect calculation of night flight time without a complete minute-by-minute breakdown of the aircraft's position over the entire flight. For modern airliners, this is potentially quite achievable and is discussed later on in the Conclusions section. However, this calculator is attempting to calculate night flight time using the flight information recorded in a pilot's logbook, which is generally quite limited and rarely if ever includes the flight's route and timings.

In order to calculate night flight time from this limited information – specifically the departure and arrival times and locations – it is necessary to create a representative model of the flight's path. The goal of this model is to allow the approximate position of the aircraft to be estimated at any given time between departure and arrival. This estimated position can then be used as the reference position for calculating the Solar Elevation, and hence determine whether the flight conditions were day or night.

Any representative model of a flight will need to make a number of assumptions about the trajectory and speed of the aircraft. These assumptions will each introduce a degree of error between the estimated and actual position of the aircraft, resulting in an error in the final calculation of night flight time. The assumptions used here are discussed below, along with the implications of each on the accuracy of the final calculation:

- Assume the flight follows a Great Circle Track from the departure position to the arrival position:

- A Great Circle track between departure and arrival positions is straightforward to calculate and offers the most practical model of the flight's path.

- Commercial aircraft in particular, are typically planned to follow the Great Circle track between departure & arrival aerodromes as closely as possible, as this represents the most efficient route for the flight.

- In practice, however, aircraft never fly a perfect Great Circle track and most, especially short-distance flights, will usually wander some way from the ideal Great Circle track. This wandering will introduce a degree of error between the estimated and actual position.

- The amount of error can be reduced by knowing the actual flight plan and using this to model the flight path, rather than assuming a Great Circle track.

- Assume the aircraft's ground speed (velocity) is constant throughout the flight:

- Without knowledge of the head or tailwinds faced during the flight, it must be assumed that the aircraft travels at a constant velocity along the Great Circle track between departure and arrival.

- In reality, the ground speed of the aircraft will vary significantly throughout the flight as a result of wind, particularly high-altitude flights that encounter jetstreams in the upper troposhere. These variations in ground speed will impact the accuracy of the modelled position.

- The error could potentially be reduced by including forecast or reported wind data for the flight.

- If no take-off or landing times are available, assume taxiing time is zero:

- For aeroplane flights, the departure and arrival times include time spent taxing on the ground when the aircraft's velocity is negligible compared to its airborne velocity.

- By assuming no ground taxiing and a constant ground speed through the flight, the aircraft is assumed to be moving towards destination from the first minute of departure, whereas in reality the flight may have had a significant period of time between departure (from the parking position) and first becoming airborne (take-off).

- This will result in significant position error between the modelled aircraft position and the actual position.

- The amount of error can be greatly mitigated by including the take-off and landing times in the flight path model, which are sometimes recorded in pilot's logbook and has therefore been included as an option in this calculator.

- Less effective mitigation is possible by assuming flights have a fixed amount of taxi-out and taxi-in times (not included).

- If take-off & landing times are available, assume ground speed during taxiing is zero:

- The aircraft's velocity during taxiing is usually negligible compared to its airborne velocity, and for practical purposes can be assumed to be zero.

- Thus, the aircraft's position along the flight path would be considered static at the departure position for the time between the departure (at the gate) and take-off.

- Likewise, it would be assumed as static at the arrival position between landing time and arrival time (at the arrival parking stand).

- This assumption will only result in a small amount of position error in the model, which will typically have an impact of only a few seconds on the final night flight calculation.

- If the departure and arrival positions are the same, assume the aircraft velocity is zero and its position is stationary for the entire flight:

- Where the departure and arrival positions are the same, it is necessary to assume the aircraft remains in one place and does not move throughout the flight.

- For flights departing & arriving from the same aerodrome, the position used shall be the Aerodrome Reference Position (see Definitions).

- In reality, most flights to/from the same point will usually travel a substantial distance from the initial departure point, and so assuming the flight is "stationary" will significantly affect the estimated position.

- As with the Great Circle assumption, the amount of error could be reduced by knowing the actual flight plan and using this to model the flight path.

- For Great Circle and solar calculations, Earth shall be assumed as spherical and it's motion purely elliptical:

- Since the earth is not quite a sphere, the spherical geometry used to calculate great circle positions and solar elevation will contain small errors.

- The earth is an oblate spheroid with a radius varying between 6,378km at the equator and 6,357km at the poles. In this calculator, the mean radius of 6,371 km is used for Great Circle calculations. This creates an error errors of up to 0.55% crossing the equator, though generally below 0.3%, depending on latitude and direction of travel.

- Whuber explores this in excellent detail here.

- Standard WGS-84 geodesic equations provide an accuracy of better than 3m in 1km, which is more than sufficient for practical purposes.

- Similarly, the motion of Earth is subject to small perturbations by the Moon and the planets. These perturbations can result in a position accuracy of 0.01 degrees.

- Both of these assumptions will introduce only a small amount of position error calculator, with a worst-case error of up to 1 minute of night flight time.

Modelling the Flight as a Great Circle Track

Without detailed knowledge of a flight's minute-by-minute position, determining the night-time portion of the flight requires the creation of a practical approximation of the aircraft's flight path. This "model" must be produced using only the parameters normally recorded in the logbook:

- Departure aerodrome or position

- Arrival aerodrome or position

- Departure time - known as "Blocks-off" or "Chocks-off"

- Arrival time - known as "Blocks-on" or "Chocks-on"

Optionally, if recorded in the logbook, the following parameters can be used to refine the model:

- Actual Take-off time

- Actual Landing time

An effective model for the flight path is the Great Circle Track, which is the shortest distance between two points on Earth. This model works particularly well for commercial flights, since for efficiency, these fights will endeavour to fly the great circle track as closely as possible.

When a flight is modelled using a great circle flight path, the average ground speed of the flight can be determined by dividing the length of the great circle by the total flight time. This then allows us to determine the approximate position of the aircraft between the departure and arrival points at any given time or distance during the flight.

The formulae used to create the great circle flight path model are listed below. These are based on Vincenty's formulae and have been adapted from Aviation Formulary by Ed Williams and latitude/longitude scripts by Chris Veness.

Calculating Great Circle Distance between two Latitude/Longitude points

The great circle distance \(d\) between two points with latitude, longitude coordinates \(\varphi_1\;,\; \lambda_1\) and \(\varphi_2\;,\; \lambda_2\) is given by: $$ d = \arccos(\sin\varphi_1 * \sin\varphi_2 + \cos\varphi_1 * \cos\varphi_2 * \cos(\lambda_1-\lambda_2)) $$

With the distance, calculate an average ground speed for the flight using the departure and arrival times \(t_1\) & \(t_2\): $$ V_{GS} = {t_2 - t_1 \over d} $$

Calculating Initial Bearing of the Great Circle Track

The initial bearing \(θ\) of the Great Circle track is the angle relative to true north at the departure point. It is used to calculate intermediate positions along the great circle flight path: $$ \theta = {atan2} \pmatrix{ \sin(\lambda_1-\lambda_2) * \cos\varphi_2 \;,\\ \cos\varphi_1*\sin\varphi_2-\sin\varphi_1*\cos\varphi_2*\cos(\lambda_1-\lambda_2) } $$

To convert the initial bearing to compass degrees: $$ \theta_{deg} \equiv \theta\mod2\pi $$

Calculating Intermediate Points along the Great Circle Flight Path

With the initial bearing, it is possible to calculate the latitude & longitude of any point along the great circle flight path, given a distance from the departure point. First, the distance \(d\) is converted to angular distance \(θ\) by dividing by Earth's mean radius \(R\): $$ \delta = d/R $$ where: \(R = 3440.0695 \) nautical miles.

From this, the latitude & longitude \(\varphi_3\;,\; \lambda_3\) of any point along the great circle path can be calculated using the departure lat/lon \(\varphi_1\;,\; \lambda_1\): $$ \varphi_3 = \arcsin({\sin\varphi_1 * \cos\delta + \cos\varphi_1 * \sin\delta * \cos\theta}) $$ $$ \lambda_3 = \lambda_1 + {atan2} \pmatrix{ \sin\theta * \sin\delta * \cos\varphi_1 \;,\\ \cos\theta - \sin\varphi_1 * \sin\varphi_3 } $$

Calculating the Sun's Elevation

According to ICAO, A flight is deemed to be taking place at night any time the Sun's geometric centre is 6 degrees or more below the horizon, ie: $$ {Solar \; Elevation} \leq -6^o $$

The formulae used to calculate Solar Elevation for a given time and position are detailed below. These have been adapted from Astronomical Algorithms (1991) by Jean Meeus.

Convert the Flight Date & Time to the Julian Century

Astronomical calculations require the date \(\{year, month, day\}\) and \(time \) (represented as a fraction of 1 day) to be converted to the equivalent Julian Date: $$ A = int \left(\frac{year}{100}\right) \\ B = 2 - A + int \left(\frac{A} {4}\right) \\ JD = int(365.25 * (year + 4716)) + int(30.6001 * (month + 1)) + day + B - 1524.5 + time $$

The Julian Date is then converted as follows to the Julian Century based on the epoch J2000: $$ T = \frac{JD - 2451545.0}{36525} $$

Calculate Earth's Obliquity & Lunar Constants

The longitude of the ascending node of the Moon's mean orbit on the ecliptic, measured from the mean equinox of the date \( \Omega \) is: $$ \Omega = 125^o.04 - 1934^o.136T $$

The mean obliquity of Earth's ecliptic \( \epsilon_0 \) is: $$ \epsilon_0 = 23^o.439291 - \frac{48.815T - 0.00059T^2 + 0.001813T^3}{3600} $$

This is corrected for nutation - the impact of the Moon on Earth's longitude \(\Delta \psi \) and obliquity \(\Delta \epsilon \). A reasonable-accuracy correction is: $$ \Delta \psi = -17".20 \sin \Omega - 1".32 \sin 2L - 0".23 \sin 2L' + 0".21 \sin 2 \Omega \\ \Delta \epsilon = +9".20 \cos \Omega + 0".57 \cos 2L + 0".10 \cos 2L' - 0".09 cos 2 \Omega $$ Where \( L \) and \( L' \) are the mean longitudes of the Sun & Moon respectively, given as: $$L = 280^o.4665 + 36000.7698T \\ L' = 218^o.3165 + 481267^o.8813T $$

Giving Earth's corrected obliquity \( \epsilon \) as: $$ \epsilon = \epsilon_0 + \Delta \epsilon $$Calculate Solar Declination & Equation of Time

The mean longitude \( L_0 \) of the Sun is: $$ L_0 = 280^o .46645 + 36 000^o .76983T + 0^o.0003032T^2 $$

The mean anomaly \( M \) of the Sun is: $$ M = 357^o.52910 + 35999^o.05030T - 0^o.0001559T^2 - 0^o.00000048T^3 $$

The Sun's equation of centre \( C \) is: $$ C = + (1^o.914600 - 0^o.004817T - 0^o.000014 T^2) \sin M \\ + (0^o.019993 - 0^o.000 101 T) \sin 2M \\ + 0^o.000 290 \sin 3M $$

The Sun's true longitude \( \Theta \) is: $$ \Theta = L_0 + C $$ And the Sun's apparent longitude \( \lambda \) is: $$ \lambda = \Theta - \Delta \psi $$

The Sun's right ascension \( \alpha \) is: $$ \alpha = atan2\pmatrix{\cos\epsilon * \sin\lambda\;, \\ \cos\lambda} $$ And the apparent declination \( \delta \) is: $$ \delta = \arcsin(\sin\epsilon * \sin\lambda) $$

This allows the Equation of Time \( E \) to be determined: $$ E=L_0 -0^o.0057183 - \alpha + \Delta\psi\cos\epsilon $$

Calculate Solar Elevation

The Equation of Time can be used to determine the Sun's elevation for any given location at any given time. This thereby allows us to determine whether the flight conditions at a particular location & time were "day" or "night".

True solar time \( ST \) is for a given time \( t_{min} \) (expressed in minutes) and longitude \( \lambda_1 \) is given as: $$ ST = t_{min} + E + 4\lambda_1 \\ if\;ST \lt 0",\;ST = ST + 1440" $$ To convert to the Hour Angle \( HA \) (expressed in degrees): $$ HA = ST /4 -180^o \\ if\;HA \lt -180^o,\;HA = HA + 360^o $$

With the corresponding latitude \( \varphi_1 \), the Sun's Zenith angle can be determined as: $$ Solar\;Zenith = \arccos(\sin\varphi_1 * \sin\delta + \cos \varphi_1 * \cos \delta * \cos HA) $$ Finally, Solar Elevation (altitude above the horizon) is: $$ Solar\;Elevation = 90^o - Solar\;Zenith $$

Iteratively Determining the Start and End of Night Time

Civil Twilight is the when the Sun's geometric centre passes through 6° below the horizon (or -6° elevation). This occurs twice daily:

- Morning Civil Twilight occurs when the Sun rises through -6° (night→day)

- Evening Civil Twilight occurs when the Sun descends through -6° (day→night)

From a fixed position on Earth, it is straightforward to calculate the time at which both Civil Twilight times will occur using Jean Meuss' equations, as detailed in the previous section. However, an aircraft flying between two destinations is constantly changing position, and so is the time at which Civil Twilight begins and ends. High speed and high latitude (polar) flights add further to the complexity; an observer stationed at a fixed position would see Morning & Evening Civil Twilight once every 24 hours, whereas a modern airliner travelling eastbound at high speed is adding substantially to Earth's natural rotation speed and will therefore reach the threshold of Civil Twilights much sooner.

Consider an long-haul flight travelling from New York (KJFK) to London Heathrow (EGLL) in northern hemisphere summer (late-June):

- The flight departs at 23:00Z, early evening in New York, still in daylight but with sunset approaching;

- Evening civil twilight begins shortly after take-off and ends (day→night) 1 hr 45 minutes into the journey;

- Continuing eastbound at high speed, the flight's movement effectively shortens already brief summer night-time period from ~8 hours to under 4 hours. The aircraft reaches the start of morning civil twilight (night→day) at 26° West longitude;

- The flight continues in daytime until landing.

Existing night flight calculators may only consider the Civil Twilight from only the departure point or arrival point of the flight, which can introduce significant error, as demonstrated in the earlier section above. A better solution is to determine exactly when sunset, sunrise and civil twilight start and end occurs during a flight. This is achieved using iteration via the method outlined below:

- Model the flight as a Great Circle Track between departure and arrival;

- Divide the modelled flight path into periodic time intervals (recommended 10 minutes);

- Determine the aircraft's position at each time interval;

- For each position, calculate the solar elevation at the corresponding time interval;

- Compare each solar elevation with the solar elevation at the previous position to see if civil twilight began or ended (or for US records, one hour since sunset/sunrise elapsed) and hence the aircraft transitioned from day to night or vice-versa;

- If a day→night or night→ transition took place, perform a finer iteration using 1-minute intervals across the 10-minute period to determine the exact minute at which the transition occurred;

- Continue iterating until the end of the flight to ensure all day→night and night→day transitions are identified;

- Add up the times when the flight was between evening civil twilight and morning civil twilight to give the total night flight time.

The animation below shows an example of the iteration steps for the proposed New York to London flight described above:

Returning the Total Night Flight Time

With the solar elevation calculated at the beginning and end of the flight, and the exact minute of each day→night and night→day transitionsion determined through iteration, the final step will be add up the portions of the flight that occurred at night and return a value to the nearest minute.

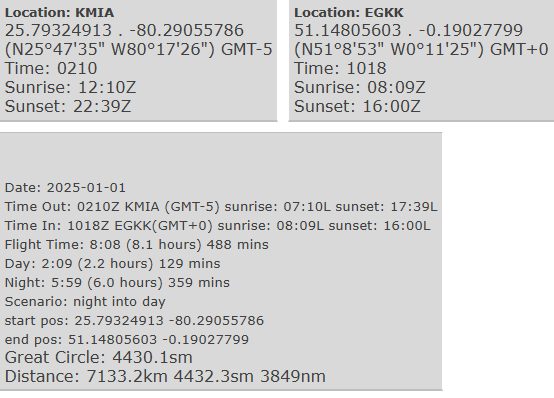

Taken together with the solar elevation at flight departure and arrival, the list of day→night and night→day transitions will look like this real-world example for a flight from Miami (KMIA) to London Gatwick (EGKK):

| Event | Time (UTC) | Solar Elevation | Position | Condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Departure KMIA (blocks-off) | 21:20 | +32.5° | N 25.793° W 80.291° | Day |

| Evening Civil Twilight ends | 23:35 | -5.8° | N 37.412° W 65.644° | Night |

| Morning Civil Twilight begins | 04:25 | -6.1° | N 51.812° W 12.609° | Day |

| Arrival EGKK (blocks-on) | 05:53 | +10.0° | N 51.148° W 0.190° | Day |

From this list, the total flight time during night is straightforward to calculate: The flight departed northeastbound during daytime and crossed into night (end of evening civil twilight) 2 hours after departure at 23:20Z, at approximately 60° West. It continued eastbound, crossing back into day (beginning of morning civil twilight) just over 5 hours later at 04:25Z, at longitude 5.8° West. The rest of the flight continued in daytime.

The night portion is that between end of evening and start of morning civil twilight was 23:20 to 04:25, or 5 hours 5 minutes.

A further example is shown below, London Heathrow EGLL to Singapore (WSSS). This example includes take-off and landing times and a transition from day to night prior to take-off:

| Event | Time | Solar Elevation | Position | Condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Departure EGLL (Blocks-off) | 2024-09-06 19:00 | -4.5° | N 51.471° W 0.462° | Day |

| Evening Civil Twilight | 2024-09-06 19:10 | -6.0° | N 51.471° W 0.462° | Night |

| Take-off | 2024-09-06 19:25 | -8.2° | N 51.471° W 0.462° | Night |

| Morning Civil Twilight | 2024-09-07 01:02 | -6.0° | N 42.556° E 60.239° | Day |

| Landing | 2024-09-07 08:20 | +40.4° | N 1.350° E 103.994° | Day |

| Arrival WSSS (Blocks-on) | 2024-09-07 08:30 | +37.9° | N 1.350° E 103.994° | Day |

In this example, the flight leaves the gate in daytime, but just before evening civil twilight ends. Night time begins during taxi-out. The model assumes the aircraft is stationary and begins iterating along the flight path after take-off at 19:25Z. The flight continues in night for just over 5 ½ hours until reaching longitude ~60° East, where morning civil twilight begins. It continues in daytime until landing and arrival.

The total night portion is the period between end of evening civil twilight during taxi for take-off, until start of morning civil twilight at ~60° East. This is 19:10 on 6 Sep to 01:02 on 7 Sep, or 5 hours 52 minutes.

Study Conclusions

The Night Flight Calculator App provided by this study is able to create a Great Circle model of a flight and use this model to calculate the portion of a flight that occurred in night conditions. It does this using only the basic flight details that make up a typical record in a pilot's logbook. As a minimum, it can calculate a reasonable approximation of night flight time based on departure time, arrival time, and departure and arrival latitude & longitude.

The calculator splits each modelled flight into 10-minute time segments, then individually analyses each segment to determine whether a day→night or night→day transition occurred. If a transition occurred, it uses a finer minute-by-minute iteration to determine the exact minute the transition occurred. Finally, it returns the total night flight time accurate to the nearest minute, based on flight conditions at the start and end of the flight, and the time of each day→night and night→day transition that occurred along the modelled flight path.

If take-off and landing times are provided, the model can also consider taxiing periods between leaving the gate to take-off, and landing to arrival at gate, adjusting the model to account for the aircraft's relatively low speed during taxi.

This technique ensures a calculation that is both sufficiently fast and reasonably practical, given the constraints of the logook dataset. The calculator performs well when compared to other existing night flight calculators, providing very similar and consistent results to both the Logbook.aero and the flylog.io calculators, which each delivered consistent and similar results during a survey of theoretical long-haul flights. It is likely that each of these calculators uses a very similar approach to flight modelling and night flight time calculation and it is hoped that the detailed description herein will be adpoted as the standard method for night flight time calculation in pilot logbooks by software developers and regulators in the future.

Automatic night flight calculation offers a huge improvement over pilot approximations, and should ideally become the norm for pilot logbooks in the 21st Century. It is equally important, however, to ensure that automatic caculators use a common approach standard that delivers a consistent result, which is presently not the case.

This calculator is provided here to assist pilots with a means of accurately approximating night flight time for their logbooks. It may also be of assistance to both aviation regulators and airline compliance auditors, allowing them to verify the accuracy of pilot logbook entries by comparing the logbook values with the modelled flight calculations.

Limitations of the Calculator

As discussed in detail in the Assumptions section above, the night flight calculator relies on a number of assumptions when creating a representative Great Circle model of a flight. These assumptions are necessary because of the limited data available from typical pilot logbook records. Given these constraints, the Great Circle model is the most practical solution available, producing smaller errors than the methods used by other existing night flight calculators. Although effective, the assumptions required by the model will introduce significant error into the final night flight time calculation, particuarly for longer flights at high altitude. Upper wind effects and differences between the Great Circle flight path and actual route flown are likely to have the most significant impact. However, in the absence of detailed knowledge of the flight path, the final calculation should provide a close approximation of the actual night flight time. Gross error is unlikely in all but the most extreme edge cases of flight conditions.

In order to ensure fast calculation times, the calculator only checks for day→night/night→day transitions every 10 minutes of the flight. It is possible, therefore, that a day→night and night→day transition could be missed if both occurred within a 10-minute time window. This might occur on certain flights at very high latitudes, where the day or night is very short, or shortend by the speed and direction of the flight. Such cases would result in a night flight time error of less than 10 minutes.

Improving the Accuracy of Night Flight Time Calculations

Some logbook tools can record a flight's flight plan, listing the waypoints along the route that the flight is planned to follow. Commercial airline pilots are also required to record the aircraft's progress versus the flight plan throughout the flight. Each of these offers an opportunity to refine the accuracy of the night flight time calculation, by using the recorded waypoints and crossing times to create a more accurate model of the flight path. This would substantially improve the accuracy of the calculations versus Great Circle modelling, as it would remove the need for several key assumptions, in particular the effect of wind on the aircraft's position.

Future Improvements to Night Flight Time Accuracy - An Appeal to Manufacturers

Although automatic calculators such as this greatly improve the status-quo, they remains limited in accuracy, due to the various assumptions required to model a flight (discussed in detail in this section). With recent improvements in aircraft flight management systems, a much better solution exists that could be used by commercial operators, as well as private flyers in the future.

Most modern commercial aircraft are fitted with a Flight Management System (FMS), which automatically manages the aircraft's navigation along a series of waypoints that make up the flight plan. The FMS continuously monitors and records the aircraft's position, direction and ground speed throughout the flight. The recorded data is used by many airlines to track the actual times of departure, arrival, take-off and landing of each flight. A real example of a post-flight report from a Boeing 787 is shown in the adjacent figure (Note: OUT, OFF, ON & IN correspond to blocks-off, take-off, landing and blocks-on times respectively. The times for each are shown under each header and are in UTC).

Even if ACARS is not used, the reporting page from the FMS can be displayed after a flight and is already used by many commercial pilots to record the flight's timing in their logbooks. However, to the author's knowledge, no FMS currently computes the flight conditions (ie: day or night) during the flight. It is therefore unable to provide a report of the actual night flight time for the pilots.

If FMS manufacturers were to add this functionality, by including the calculation steps discussed in this section, it would be possible for the FMS to record the day or night condition on a minute-by-minute basis throughout each flight. Given the precision of modern FMS position calculations and their internal GPS-linked clocks, these night time calcuations would be accurate to within seconds, far superior to any technique that relied on flight modelling, as it would not have need for most of the assumptions that underpin modelling techniques.

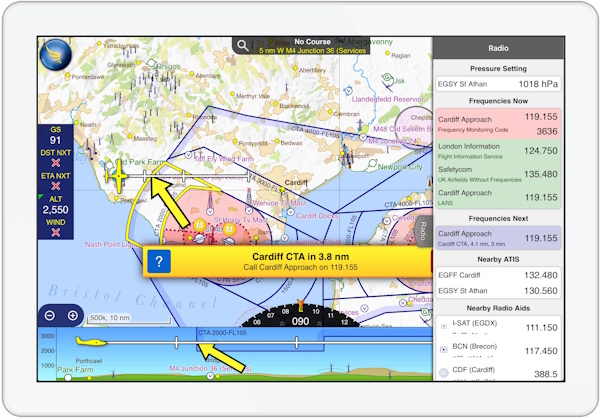

For private pilots and aircraft without FMS systems, a solution may be available in the form of tablet-based electronic flight bag applications. These applications are increasingly popular among private pilots, and typically use the tablet's built-in GPS receiver to track the position of the aircraft in flight. Many will provide alerts to the pilot – the adjacent figure shows an example alert from the SkyDemon application.

A relatively straightforward software feature could be added within these applications, which would continuously monitor the day/night conditions throughout the flight's journey and alert the pilot once night time begins or ends. The accumulated night-time could also perhaps be provided to the pilot, either on a continuous basis or in a post-flight report. Likewise with the commercial FMS, this would also provide a much more accurate calculation of night flight time.

Appeals are therefore made to airliner FMS manufacturers and EFB application developers to consider adding this functionality in future versions of their software. It would significantly improve the ease and accuracy of night flight time recording for pilots worldwide and represents the ideal solution for the industry.